Math and physics rarely fail students because of a lack of intelligence. Trouble usually starts much earlier, at the moment a dense paragraph or symbolic expression lands on the page and stays fuzzy in the mind.

Strong problem solvers share one reliable habit. They turn messy prompts into a clean structure before touching serious algebra.

A good solution is rarely accidental. It grows from a repeatable process that translates words into variables, selects a model with clear assumptions, and checks the result with the same care an engineer gives a design.

Research in math education, physics education, and cognitive science all point in the same direction. Skill comes from method, not shortcuts.

Today, we prepared a field-tested set of techniques used by expert solvers and supported by decades of research. Every idea below is practical.

Every one can be applied immediately, whether the task is a calculus exam, a mechanics problem set, or a mixed final that refuses to stay in one lane.

What Expert Problem Solvers Do Differently

Across STEM education, a consistent pattern shows up. Experts group problems by deep structure, meaning the underlying principles that govern a situation. Novices group problems by surface features, meaning what the problem looks like at first glance.

In physics, an expert sees conservation of energy or Newton’s laws. A novice sees an inclined plane or a pulley. In math, an expert sees symmetry, a quadratic structure, or an invariant. A novice sees a word problem with numbers that look unfamiliar.

Surface features change constantly. Core principles change rarely. Training the expert habit requires two deliberate moves:

Making those moves shifts problem-solving from guesswork to control.

Also, if you want targeted practice that reinforces recognizing deep structure, try Qui Si Risolve.

A Repeatable 5-Step Problem-Solving Loop

One of the most researched workflows in physics education comes from Cooperative Group Problem Solving, associated with Heller and colleagues. The structure mirrors how experts work in real time. The same loop fits math problems just as well.

Step 1: Visualize the Situation

Visualization does not require artistic talent. A quick sketch, a number line, a graph shape, or a geometric outline is enough.

Physics example, forces on a block:

Common force set:

- Weight: W = m*g

- Normal force: N

- Friction: f = mu*N

Math example:

A sketch anchors abstract symbols to something concrete.

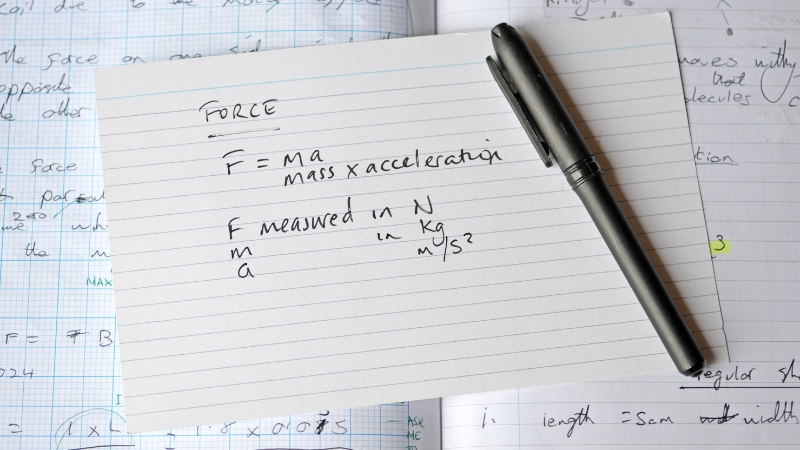

Step 2: Describe the Problem in the Language of the Subject

Rewrite the question using symbols and relationships.

- Known: h = 3 m, g = 9.8 m/s^2

- Target: v

- Model: constant acceleration, starting from rest

That translation clarifies what the problem is really asking.

Step 3: Plan a Route Before Doing Algebra

Planning means choosing tools before calculating.

Physics planning options:

- Newton’s 2nd law: F_net = m*a

- Kinematics: v^2 = v0^2 + 2aΔx

- Energy: K_i + U_i = K_f + U_f

Math planning options:

- Algebraic manipulation

- Factoring

- Substitution

- Symmetry

- Known theorems

A short plan prevents wandering.

Step 4: Execute Cleanly and Track Logic

Most lost points come from rushed algebra, sign errors, or undefined quantities. Clean execution means slow enough to stay consistent.

Step 5: Evaluate the Result Like a Scientist

Evaluation is part of the method, not an optional extra.

Checks to run:

Many incorrect answers look correct until this step exposes them.

Technique 1: Translate Words Into a Known–Target–Constraints List

@youwantalgebra Constraints and solving ##fyp##youwantalgebra##mathtutor##mathhelp##mathteacher##gedmath##algebra##psatprep##satprep##actprep##8thgrademath##algebra1##constraints##solveforx ♬ original sound – YouWantAlgebra

Before equations, write three lines.

- Knowns: given numbers and relationships

- Target: the quantity to find

- Constraints: conditions such as no friction or real solutions

Math example:

- Known: x + y = 12, x*y = 35

- Target: x, y

- Constraints: real numbers

Physics example:

- Known: v0 = 20 m/s, theta = 30°, g = 9.8 m/s^2

- Target: range or time

- Constraints: neglect air resistance

That short list prevents solving the wrong problem.

Technique 2: Build the Model-First Habit

Every equation carries assumptions. Many math tools do as well.

Ask a simple question before writing formulas:

Physics model examples:

- Constant acceleration near Earth

- Point mass approximation

- Energy conservation without nonconservative work

- Ideal circuit behavior

Math model examples:

- Local linear behavior

- Symmetry arguments

- Systems of equations

- Recursive definitions

Frederick Reif’s research shows that effective problem solving depends on choosing the right knowledge structure, then applying it with control.

Technique 3: Use Multiple Representations Early

Strong solvers move fluidly between words, diagrams, graphs, tables, and equations.

Physics education research repeatedly shows that explicit diagram use improves accuracy and speed.

Examples:

Math:

- Sketch a function to predict roots and turning points

Physics:

- Draw initial and final states for energy problems

- Label heights, speeds, and reference levels

A representation often reveals the governing principle faster than calculation.

Technique 4: Do a Principle Sort Before Solving

Train expert categorization deliberately. Before solving, label the problem.

Physics categories:

- Newton’s laws

- Energy conservation

- Momentum conservation

- Rotational dynamics

- Field laws

Math categories:

- Factorization and identities

- Symmetry and invariants

- Optimization

- Counting

- Geometry

Write a one-line label at the top of the page, such as “Category: energy conservation.” That small habit keeps method selection intentional.

Technique 5: Reduce Cognitive Load With an Equation Map

Mental overload happens when too many symbols float unconnected. An equation map fixes that.

Example: Find the speed after dropping a height h.

Possible equations:

Map the target symbol v to known quantities and choose the shortest path.

The same idea works in math. Map variables and constraints before manipulating equations.

Technique 6: Work Backwards From the Target

Experts often start with the desired quantity and trace backward.

Physics example:

Target v appears in:

Choose the form that matches known values.

Math example:

Working backward narrows the field quickly.

Technique 7: Use Simpler Versions and Extreme Cases

“It is better to solve one problem five different ways, than to solve five problems one way.” -George Polya https://t.co/n1fBEkiTXy pic.twitter.com/WNizoAFlNv

— Brainingcamp (@brainingcamp) April 18, 2018

George Polya emphasized solving related, simpler problems as a powerful move.

Simpler versions:

Math:

- Try small values

- Remove parameters temporarily

Physics:

- Set friction to 0

- Use angles of 0° or 90°

Extreme case checks after solving:

These checks catch correct algebra paired with incorrect reasoning.

Technique 8: Dimensional Analysis and Unit Discipline

Units act as an automatic error detector.

Key units:

- Force: kg*m/s^2

- Energy: kg*m^2/s^2

- Momentum: kg*m/s

If a velocity comes out in m/s^2, something broke. Dimensional analysis also flags illegal expressions, such as taking a logarithm of a quantity with units.

Technique 9: Fast Answer-Sense Checks

Spend 15 seconds after finishing.

- Sign: should it be positive

- Scale: is the magnitude reasonable

- Bounds: probabilities between 0 and 1

- Trends: does output increase when input increases

Heller’s framework treats evaluation as essential, not optional.

Technique 10: Metacognitive Control

Alan Schoenfeld identifies four drivers of success in math problem solving:

Control means monitoring progress.

Every few lines, pause and ask:

- Do I know where this is going

- Do equations match unknowns

- Am I solving the asked question

That pause prevents confident wrong solutions.

Technique 11: Retrieval Practice for Formulas and Methods

Cognitive science research by Dunlosky and colleagues identifies practice testing and spaced practice as high-utility learning strategies.

Apply retrieval practice like this:

Physics benefit:

- Rapid recall of relationships such as F_net = m*a and v^2 = v0^2 + 2aΔx

Math benefit:

- Fluent recall of identities and transformations

Technique 12: Spacing and Interleaving

Blocked practice feels productive. Mixed practice builds transfer.

Interleaving mixes problem types so method selection becomes part of the task. Research on interleaved math practice shows stronger long-term performance compared with blocked sets.

A weekly structure:

Technique 13: Peer Explanation as a Tool

Peer Instruction research in physics shows significant conceptual gains, including improved Force Concept Inventory scores.

Use the same idea solo:

Explanation exposes gaps, silent calculation hides.

A Toolkit of Techniques and When to Use Them

| Technique | Best For | What It Prevents | Quick Use |

| Known–Target–Constraints | Word problems | Solving the wrong task | 30-second setup |

| Multiple representations | Geometry, mechanics | Equation hunting | Diagram plus labels |

| Principle sorting | Mixed sets | Wrong method | Label principle |

| Equation map | Multi-variable tasks | Overload | Draw symbol links |

| Working backward | Target-heavy tasks | Wandering | Start with target |

| Dimensional analysis | Physics | Unit errors | Check every line |

| Extreme cases | Modeling | Hidden flaws | Test limits |

| Retrieval practice | Exams | Forgetting | Recall first |

| Interleaving | Transfer | Pattern matching | Mix problems |

| Explanation | Concept mastery | Shallow work | Teach it |

Walkthrough Example 1: Physics With the Full Loop

Problem: A 2 kg object starts from rest and slides down a frictionless ramp from a height of 5 m. Find speed at the bottom.

Visualize: Ramp, start at height h, end at the bottom.

Describe:

- Known: m = 2 kg, h = 5 m, g = 9.8 m/s^2

- Target: v

Plan: Energy conservation.

Execute:

mgh = (1/2)mv^2

m cancels

v^2 = 2gh

v = sqrt(2gh)

Compute:

v = sqrt(98) ≈ 9.9 m/s

Evaluate:

Walkthrough Example 2: Math With Control

Problem: Solve x + 1/x = 5 for real x.

Known–Target:

- Equation given

- Target: x

- Constraint: x ≠ 0

Plan: Multiply by x.

Execute:

x^2 + 1 = 5x

x^2 – 5x + 1 = 0

Solve:

x = (5 ± sqrt(21))/2

Evaluate:

Common Failure Modes and Fast Fixes

- Equation grabbing – Fix: label the principle first.

- Algebra slips late in the solution – Fix: slow substitutions and micro-checks.

- Mixing similar methods – Fix: interleaved practice.

- Weak conceptual base – Fix: explanation-based practice.

A 30-Minute Daily Routine That Works

Based on retrieval practice, spacing, and structured solving:

- 10 minutes: recall formulas and one conceptual question

- 15 minutes: one full problem using the 5-step loop

- 5 minutes: error log

Write one line for each error:

An error log trains control, the most overlooked skill in problem-solving.

Final Thoughts

Problem-solving in math and physics rewards structure, patience, and deliberate control. Talent matters far less than method. Build a repeatable loop, choose principles before equations, and treat evaluation as part of the solution.

A similar mindset shapes many trade school careers, where clear processes, hands-on repetition, and practical judgment matter more than abstract theory alone.

Over time, messy prompts start to feel manageable, and difficult problems become familiar terrain rather than a wall.